Katherine Baird

Growing Mangos In the Desert

Excerpt

Prologue

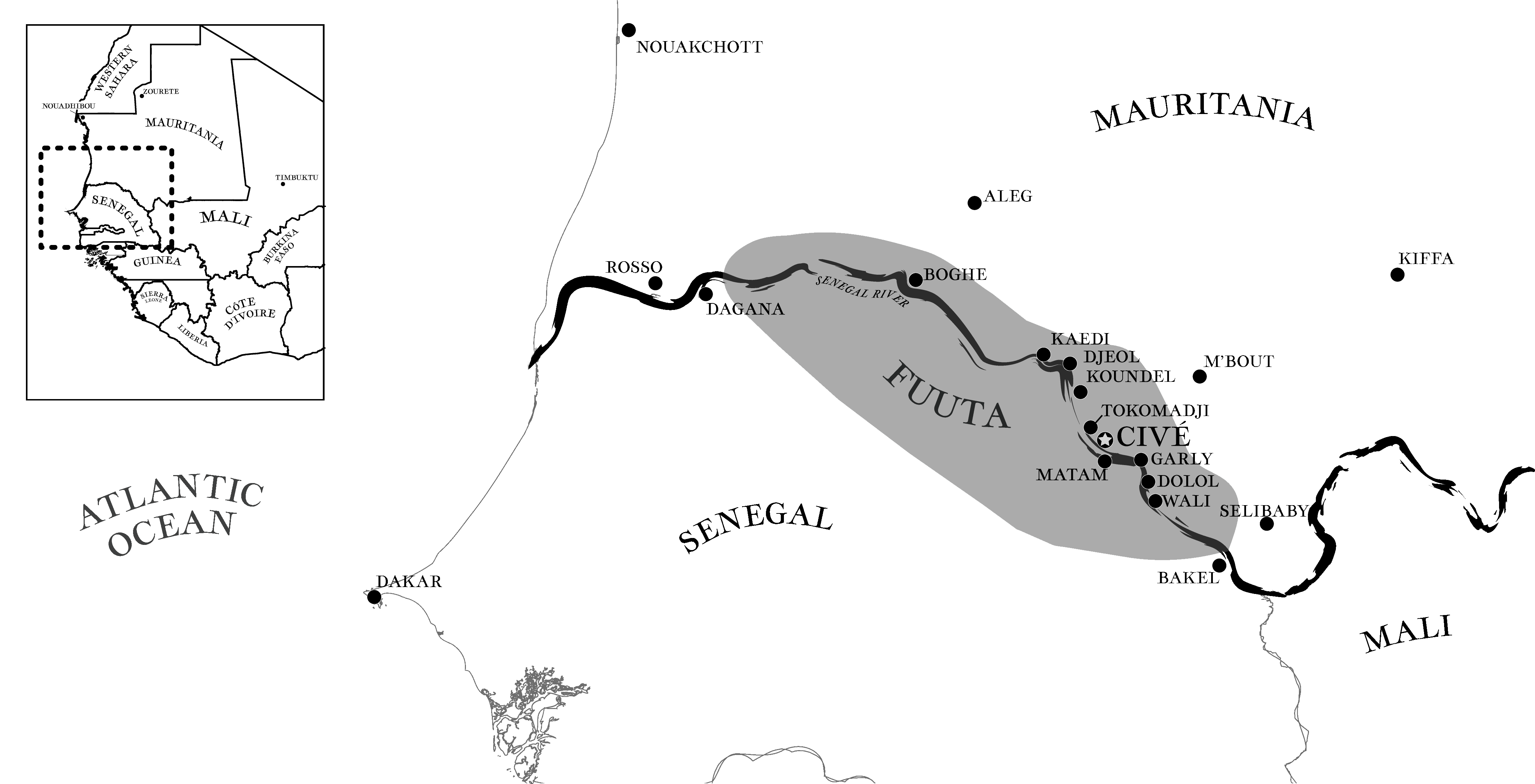

In 1984, I settled into a small Mauritanian village located along a 300-mile stretch of the Senegal River referred to as the Fuuta Toro—Fuuta for short. As a Peace Corps volunteer, my mission in Civé was to help villagers grow rice in new irrigated perimeters built with foreign dollars. These perimeters represented international communities’ help in tackling a two-decade long drought that ravaged the region.

Unfortunately, my assignment was not particularly well thought out, as even with a crash course in rice cultivation, I knew desperately little about a livelihood on which so many here depended. As if that wasn’t enough, the words and actions of all those in Civé swirled about, leaving me as baffled as did the posse of donkeys that arrived at my gate each morning braying urgent messages my way.

Decades later, I marvel at my pluck, plunging as I did into the unknown, convinced that with good intentions I would make a difference in this suffering land. And yet, against all odds I did make a difference. Or so at least I thought.

In 1987, I left the village of Civé, happy with my accomplishments as I headed for a master’s program in agricultural economics. My plan was to return to Africa, maybe even this exact bend in the river, and continue working to lift poor rural communities like Civé up from poverty.

But like many bright plans of youth, mine were first dimmed by detours, then snuffed out by the passage of time. A few years after I left Mauritania, a violent civil war broke out and my accomplishments there suffered the fate of clothes hanging to dry as the cartwheeling Harmattan winds storm through.

Eventually, my master’s degree segued into a PhD, then came a wonderful husband, two darling boys, and a coveted faculty position at the University of Washington. One March day in 2012, I sat in my living room grading papers. The phone rang. Five minutes later, the call ended. My chest ached. News had reached me that my dear friend in Civé, Mamadou Konaté, just died.

For days I silently mourned Mamadou’s passage. The fact that he would have no obituary stung. If anyone deserved one, it was Mamadou. So, I began writing a eulogy. I spent days scouring my basement for the tattered spiral notebooks that served as daily companions during my time in Civé. One after another, I read the vivid detail they contained and relived my thirty stressful and emotional months in Civé.

To my surprise, one of the first entries I scribbled made note of some imposing man named Mamadou Konaté who had just visited my hut. His rude manners had irritated me, especially after he announced that I would bring fruit trees to his village. I penned with confidence my determination to resist him, as well as all future demands I was sure would be forthcoming from this arrogant fellow.

In one of my last entries, written after I had worked tirelessly by Mamadou’s side to secure Civé’s new fruit trees, I recorded a visit to the rocky uprising cradling the village, a place named Dow Hayre. A friend from the regional capital had come to say goodbye, and we were enjoying the sweeping view of Civé below, with the flat dusty nation of Senegal spreading to the south. I told him of my intent to write a book about Civé.

“Put a picture of this view on the cover,” Hyder advised me as he scooped up a handful of small laterite rocks, and then took a deep breath as he scanned the horizon.

Rarely do any of us from rich countries get to know the poor in poor ones, except maybe to hear that they are trying to infiltrate our (increasingly walled) borders. For most of us, they remain nameless and numerous, often depicted in newspaper articles and donation pitches as victims desperate for change. I am lucky. When I think of them, I see faces, feel characters, and hear deep peals of laughter. To them, my unexpected appearance amidst them was probably like that of a swaddled infant left by some wayward pelican. I was curious, odd, and brought great hope of new entertainment. What choice did they have but to shrug at my appearance, then make me part of the local scene?

And so, they did.

Decades later, I now awake each morning to Facebook messages from the children and grandchildren of my friends in Civé, asking if I spent the night in peace. By writing this book, I hope the reader will also come to wonder if those in Civé spent the night in peace. I also hope to convey how the deep inequalities that mark our planet shape both our own privileged lives, as well as the lives of those in places like Civé.

Mostly, though, I hope to have provided Mamadou with the obituary his life deserves.